Income tax is a large revenue source for the United States government. While tax rates have changed many times, since the 1860’s, the United States has used a “progressive” tax code. A progressive tax code means that people who make more money are taxed at a higher rate than those who make less money. Our progressive tax system works by placing earners through different brackets according to how much money they make. The dollar amounts define your tax brackets and there are differing tables depending on your filing status (single, married, etc.). This matters in determining your marginal tax rate.

Understanding Marginal Tax Rates

Determining your tax bracket is not as simple as just adding up your total income and checking a tax table. Taxpayers need to calculate their taxable income (which can be sometimes referred to as their “adjusted gross income”) and then adjust their income for any deductions, adjustments and exemptions they are allowed to find their final taxable amount.

Once you determine your final taxable income amount, it’s critical to know that not all of your income was taxed at the same rate. So, for example if you are married filing jointly, your first $19,400 is taxed at 10%. If these same tax filers have a final taxable income of $95,000, then these taxpayers are in a “marginal tax bracket” of 22%. The key thing to note is that in this example, the last dollar earned is taxed at that 22% tax rate.

2019 Tax Law Updates

For 2019, Form 1040 has been slightly redesigned. There is time to look into tax planning ideas for your 2020 taxes, but here are some things that 2019 tax filers should review. They include:

- Tax brackets have been slightly adjusted.

- The standard deductions have risen from 2018.

- There are still caps to state and local tax (SALT) deductions.

- There are new deduction rates for medical expenses.

- Capital gains will still impact your income.

- There is still a 3.8% Medicare Investment Tax.

- Charitable donations are still deductible.

- You might still be able to contribute to retirement plans (or take an RMD) if appropriate.

2019 Tax Tables and Tax Rates

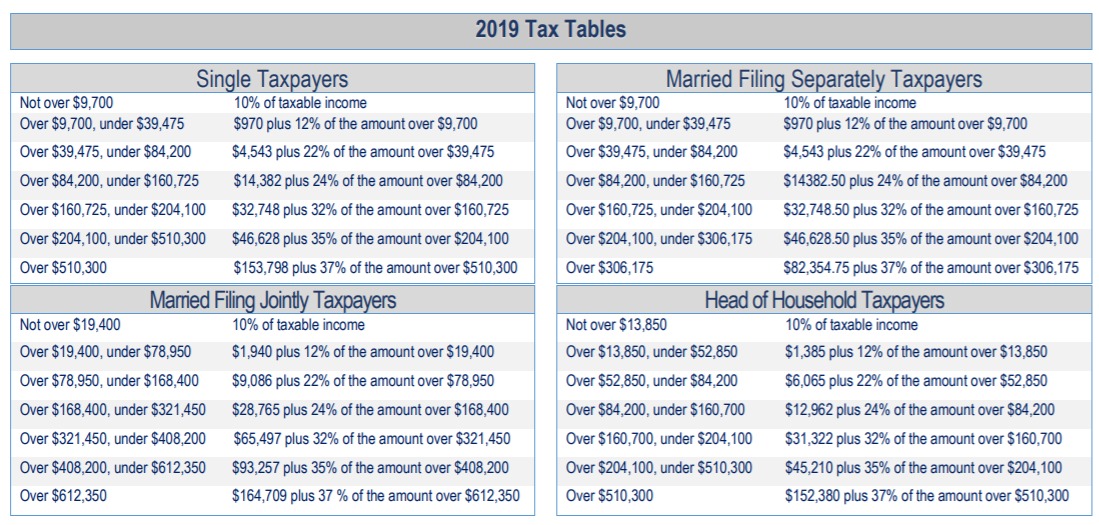

There are still seven federal income tax brackets for 2019. The lowest of the seven tax rates is 10% and the top tax rate is still 37%. The income that falls into each is scheduled to be adjusted in 2020 for inflation. For 2019, use the chart in this report to see what bracket your final income falls into.

TAX TIP: If you are not sure how best to file, ask your tax preparer or review IRS Publication 17, Your Federal Income Tax, which is a complete tax resource. It contains helpful information such as whether you need to file a tax return and how to choose your filing status.

2019 Standard Deduction Amounts

Most taxpayers claim the standard deduction. For 2019, the standard deduction has slightly increased. The amounts are now $12,200 for single filers and $24,400 for those filing jointly ($18,350 for head of household filers). If you are filing as a married couple, an additional $1,300 is added to the standard deduction for each person age 65 and older. If you are single and age 65 or older, an additional deduction of $1,650 can be made.

Increased Child Tax Credit

For 2019, the maximum child tax credit is $2,000 per qualifying child. Up to $1,400 of the Child Tax Credit is refundable; that is, it can reduce your tax bill to zero and you might be able to get a refund on anything left over. There is also a non-refundable credit of $500 for dependents other than children. The modified adjusted gross income threshold at which the credit begins to phase out is $200,000 and $400,000 if married filing jointly.

State and Local Tax (SALT) Deduction

2019 also continues the changes to state and local tax deductions that cap a taxpayer’s state and local tax (SALT) deduction at $10,000. This includes both state income and property taxes. This change affected a large number of taxpayers who live in states with high property taxes and those who pay larger state income tax bills.

Medical Expense Deduction

In late December 2019, legislation retroactively made the 7.5% threshold available to taxpayers in 2019 and 2020. The 10% threshold amount was postponed until 2021.

Investment Income

Long-term capital gains are taxed at more favorable rates compared to ordinary income. For qualified dividends, investors will continue to be taxed at 0, 15 or 20%.

One tax strategy is to review your investments that have unrealized long-term capital gains and sell enough of the appreciated investments in order to generate enough long-term capital gains to push you to the top of your federal income tax bracket. This strategy could be helpful if you are in the 0% capital gains bracket and do not have to pay any federal taxes on this gain. Then, if you want, you can buy back your investment the same day, increasing your cost basis in those investments. If you sell them in the future, the increased cost basis will help reduce long-term capital gains. You do not have to wait 30 days before you buy back this investment—the 30-day rule only applies to losses, not gains.

Note: This non-taxable capital gain for federal income taxes might not apply to your state.

TAX TIP: Remember that marginal tax rates on long-term capital gains and dividends can be higher than expected. The 3.8% surtax can raise the effective rate to 18.8% for single filers with income from $200,000 to $434,550 and 23.8% for single filers with income above $434,550. It can raise the effective rate to 18.8% for married taxpayers filing jointly with income from $250,000 to $488,850 and to 23.8% for married taxpayers filing jointly with income above $488,850.

Calculating Capital Gains and Losses

With all of these different tax rates for different types of gains and losses in your marketable securities portfolio, it’s probably a good idea to familiarize yourself with some of the rules:

- Short-term capital losses must first be used to offset short-term capital gains.

- If there are net short-term losses, they can be used to offset net long-term capital gains.

- Long-term capital losses are similarly first applied against long-term capital gains, with any excess applied against short-term capital gains.

- Net long-term capital losses in any rate category are first applied against the highest tax rate long-term capital gains.

- Capital losses in excess of capital gains can be used to offset up to $3,000 ($1,500 if married filing separately) of ordinary income.

- Any remaining unused capital losses can be carried forward and used in the same manner as described above.

TAX TIP: Please remember to look at your 2018 income tax return Schedule D (page 2) to see if you have any capital loss carryover for 2019. This is often overlooked, especially if you are changing tax preparers.

Please double-check your capital gains or losses. If you sold an asset outside of a qualified account during 2019, you most likely incurred a capital gain or loss. Sales of securities showing the transaction date and sale price are listed on the 1099 generated by the financial institution. However, your 1099 might not show the correct cost basis or realized gain or loss for each sale. You will need to know the full cost basis for each investment sold outside of your qualified accounts, which is usually what you paid for it, but this is not always the case.

3.8% Medicare Investment Tax

The year 2019 is the seventh year of the net investment income tax of 3.8%. It is also known as the Medicare surtax. If you earn more than $200,000 as a single or head of household taxpayer, $125,000 as married taxpayers filing separately or $250,000 as married joint return filers, then this tax applies to either your modified adjusted gross income or net investment income (including interest, dividends, capital gains, rentals, and royalty income), whichever is lower. This 3.8% tax is in addition to capital gains or any other tax you already pay on investment income.

A helpful strategy has been to pay attention to timing, especially if your income fluctuates from year to year or is close to the $200,000 or $250,000 amount. Consider realizing capital gains in years when you are under these limits. The inclusion limits may penalize married couples, so realizing investment gains before you tie the knot may help in some circumstances. This tax makes the use of depreciation, installment sales, and other tax deferment strategies suddenly more attractive.

Medicare Health Insurance Tax on Wages

If you earn more than $200,000 in wages, compensation, and self-employment income ($250,000 if filing jointly, or $125,000 if married and filing separately), the Affordable Care Act levies a special 0.9% tax on your wages and other earned income. You’ll pay this all year as your employer withholds the additional Medicare Tax from your paycheck. If you’re self-employed, plan for this tax when you calculate your estimated taxes.

If you’re employed, there’s little you can do to reduce the bite of this tax. Requesting non-cash benefits in lieu of wages won’t help—they’re included in the taxable amount. If you’re self-employed, you may want to take special care in timing income and expenses (especially depreciation) to avoid the limit.

Charitable Gifts and Donations

When preparing your list of charitable gifts, remember to review your checkbook register so you don’t leave any out.

Everyone remembers to count the monetary gifts they make to their favorite charities, but you should count noncash donations as well. Make it a priority to always get a receipt for every gift. Keep your receipts. If your contribution totals more than $250, you’ll also need an acknowledgement from the charity documenting the support you provided. Remember that you’ll have to itemize to claim this deduction, but when filing, the expenses incurred while doing charitable work often is not included on tax returns.

You can’t deduct the value of your time spent volunteering, but if you buy supplies for a group, the cost of that material is deductible as an itemized charitable donation. You can also claim a charitable deduction for the use of your vehicle for charitable purposes, such as delivering meals to the homebound in your community or taking your child’s Scout troop on an outing. For 2019, the IRS will let you deduct that travel at .14 cents per mile.

Child and Dependent Care Credit

Millions of parents claim the child and dependent care credit each year to help cover the costs of after-school daycare while working. Some parents overlook claiming the tax credit for childcare costs during the summer. This tax break can also apply to summer day camp costs. The key is that for deduction purposes, the camp can only be a day camp, not an overnight camp. So, If you paid a daycare center, babysitter, summer camp, or other care provider to care for a qualifying child under age 13 or a disabled dependent of any age, you may qualify for a tax credit of up to 35% of qualifying expenses of $3,000 for one child or dependent, or up to $6,000 for two or more children.

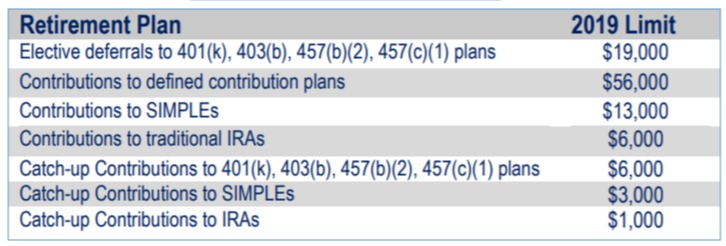

Contribute to Retirement Accounts

If you haven’t already funded your retirement account for 2019, consider doing so by April 15, 2020. That’s the deadline for contributions to a traditional IRA (deductible or not) and a Roth IRA. However, if you have a Keogh or SEP and you get a filing extension to October 15, 2020, you can wait until then to put 2019 contributions into those accounts. To start tax-advantaged growth potential as quickly as possible, however, try not to delay in making contributions. If eligible, a deductible contribution will help you lower your tax bill for 2019 and your contributions can grow tax deferred.

To qualify for the full annual IRA deduction in 2019, you must either: 1) not be eligible to participate in a company retirement plan, or 2) if you are eligible, there is a phase-out from $64,000 to $74,000 for singles and from $103,000 to $123,000 for married taxpayers filing jointly. If you are not eligible for a company plan but your spouse is, your traditional IRA contribution is fully deductible as long as your combined gross income does not exceed $193,000. For 2019, the maximum IRA contribution you can make is $6,000 ($7,000 if you are age 50 or older by the end of the calendar year). For self-employed persons, the maximum annual addition to SEPs and Keoghs for 2019 is $56,000.

Although contributing to a Roth IRA instead of a traditional IRA will not reduce your 2019 tax bill (Roth contributions are not deductible), it could be the better choice because all qualified withdrawals from a Roth can be tax-free in retirement. Withdrawals from a traditional IRA are fully taxable in retirement. To contribute the full $6,000 ($7,000 if you are age 50 or older by the end of 2019) to a Roth IRA, you must earn $122,000 or less a year if you are single or $193,000 if you’re married and file a joint return.

If you have any questions on retirement contributions, please call us.

Roth IRA Conversions

A Roth IRA conversion is when you convert part or all of your traditional IRA into a Roth IRA. This is a taxable event. The amount you converted is subject to ordinary income tax. It might also cause your income to increase, thereby subjecting you to the Medicare surtax. Roth IRAs grow tax-free and qualified withdrawals are tax-free in the future, a time when tax rates might be higher.

Whether to convert part or all of your traditional IRA to a Roth IRA depends on your particular situation. It is best to prepare a tax projection and calculate the appropriate amount to convert. Remember—you do not have to convert all of your IRA to a Roth. Roth IRA conversions are not subject to the pre-age 59½ penalty of 10%.

Many 401(k) plan participants can convert the pre-tax money in their 401(k) plan to a Roth 401(k) plan without leaving the job or reaching age 59½. There are a number of pros and cons to making this change. Please call us to see if this makes sense for you.

Required Minimum Distributions (RMD)

If you turned age 70½ during 2019, you still have until April 1, 2020, to take out your first RMD. This is a one-time opportunity in case you forgot the first time. The deadline for taking out your RMD in the future will be December 31 of each year. If you do not pay out your RMD by this deadline, you may be subject to a 50% penalty on the amount you were supposed to take out. Starting in 2020 the SECURE Act changed the starting RMD age to 72. If you have any questions on your Required Minimum Distributions please call us.

Other Overlooked Tax Items and Deductions

Reinvested Dividends – This isn’t a tax deduction, but itis an important calculation that can save investors a bundle. Former IRS commissioner Fred Goldberg told Kiplinger magazine for their annual overlooked deduction article that missing this break costs millions of taxpayers a lot in overpaid taxes.

Many investors have mutual fund dividends that are automatically used to buy extra shares. Remember that each reinvestment increases your tax basis in that fund. That will, in turn, reduce the taxable capital gain (or increases the tax-saving loss) when you redeem shares. Please keep good records. Forgetting to include reinvested dividends in your basis results in double taxation of the dividends once in the year when they were paid out and immediately reinvested and later when they’re included in the proceeds of the sale.

If you’re not sure what your basis is, ask the fund or us for help. Funds often report to investors the tax basis of shares redeemed during the year. Regulators currently require that for the sale of shares purchased, financial institutions must report the basis to investors and to the IRS.

Student-Loan Interest Paid by Parents – Generally, you can deduct interest only if you are legally required to repay the debt. But if parents pay back a child’s student loans, the IRS treats the transactions as if the money were given to the child, who then paid the debt. So as long as the child is no longer claimed as a dependent, the child can deduct up to $2,500 of student-loan interest paid by their parents each year. (The parents can’t claim the interest deduction even though they actually foot the bill because they are not liable for the debt).

Charitable Gift Directly made from IRA – Individuals at least 70½ years of age can still exclude from gross income qualified charitable distributions (QCD) from IRAs of up to $100,000 per year. Please remember to double check on what counts as a qualified charity and distribution before using this tax strategy.